A different tune – music, identity and resistance in far west China by Nick Holdstock

10th March 2015Author Nick Holdstock explores musical traditions and pop sensibilities in Xinjiang, China.

Before 2009 few people had heard of the Uyghurs, a predominantly Muslim ethnic group principally located in Xinjiang, a region in western China. This changed after July 2009, when rioting broke out in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, which led to at least 200 deaths. Though the Chinese government was quick to blame the incident on Islamic terrorists intent on getting Xinjiang to secede from China, most academics and human rights campaigners explained the violence in terms of the resentment felt by many Uyghurs towards Chinese government policies in Xinjiang.

Since the late 1970s, when the state began to initiate economic reforms throughout China, Uyghurs have become increasingly marginalised within Xinjiang, most visibly in demographic terms (before 1949, they accounted for about 90% of the region’s population; today they are less than half). Uyghurs are systematically excluded from the region’s main agricultural and industrial sectors, are over-represented in low income jobs, and are subject to widespread discrimination by employers. Their religious practices have been repeatedly targeted by the authorities, while Uyghur musicians, writers, and academics have been arrested for producing work of an apparently ‘separatist’ nature.

Over the last five years there has been an increasing number of violent incidents in Xinjiang (or at least linked to it), most notably knife attacks in April 2014 at a railway station in southwest China that led to more than 30 deaths. This violence has meant that Xinjiang, and Uyghurs, now receive far more coverage in the international media, most of which emphasises the animosity between Uyghurs and Han Chinese (the ethnic majority in China) in Xinjiang, often with the implicit assertion that this explains the rise in violent incidents in (a claim questioned by some experts).

Unfortunately, less media attention has been paid to issues and concerns within Uyghur communities in Xinjiang that do not directly relate to ethnic conflict. Only rarely is there any acknowledgement that Uyghurs might have ways to express and explore the problems faced by their communities that do not involve violence. Of these, music has perhaps the widest impact. The Uyghur classical tradition remains popular, at the core of which is the muqam, a large repertoire of sung stories and poems, instrumental passages and dance tunes. These are usually performed by a small ensemble of singers, accompanied by lutes and a drum.

However, the most popular music in Xinjiang relies on more modern musical forms, with many Uyghur artists borrowing from both regional and international musical styles. Music from Turkey, Russia, Uzbekistan and other Central Asian states is often played in shops, nightclubs and restaurants in Xinjiang, as well as some Western music.

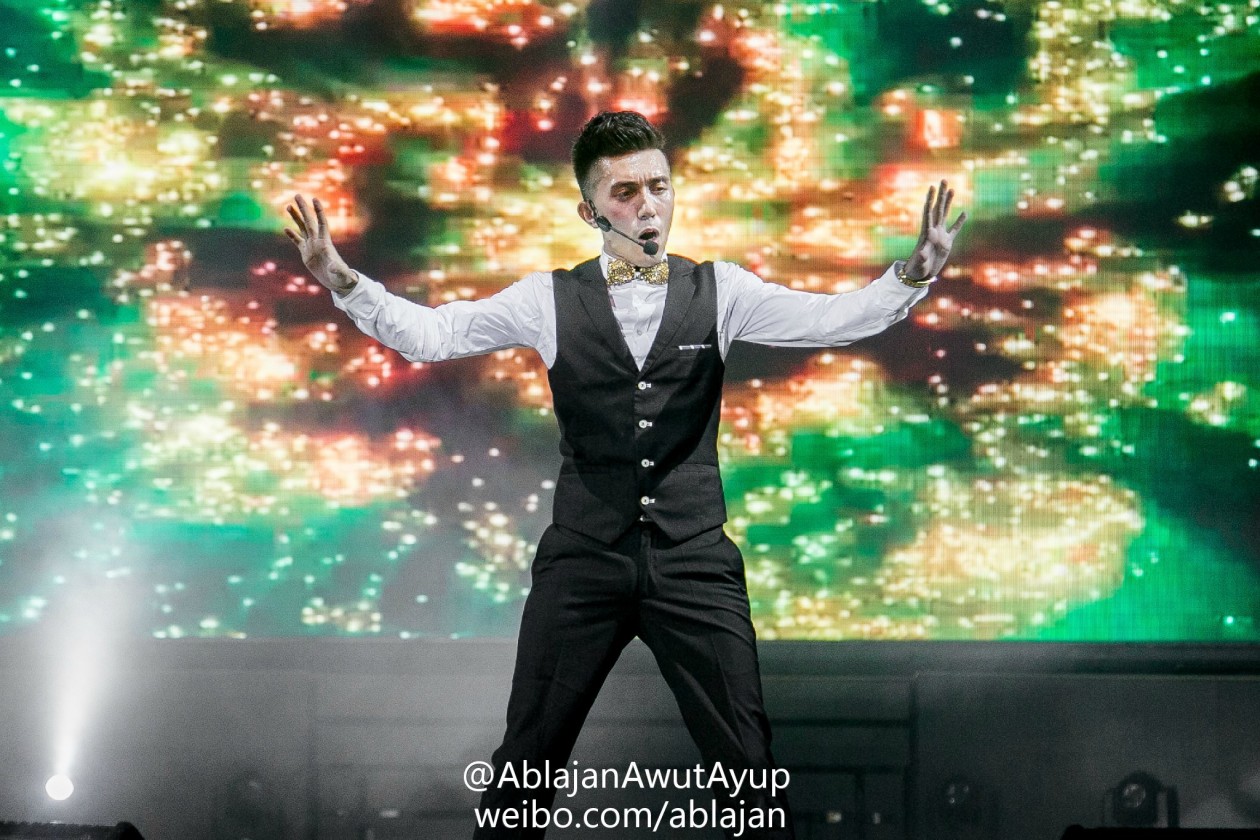

Given the plurality of the musical influences that exist in Xinjiang, it’s unsurprising that a lot of the new music in Xinjiang has both a global and local quality. No one exemplifies this better than Ablajan, a 30 year-old singer who grew up in a small village, and is often compared to Justin Bieber for his upbeat, catchy songs aimed at Uyghur children and young teenagers. His music is influenced by Uyghur folk, Sufi poetic forms, and other Central Asia influences. His stage performances owe a lot to Korean pop and the dance moves of Michael Jackson. He first saw the latter on TV when he was 14, after which he started practicing the moonwalk and writing songs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mc0Y889icdo

At 19, he went to Urumqi to study dance, and despite having no formal training or connections in the music industry, was eventually able to get a record deal. Ablajan’s first album sold more than 100,000 copies, which is a lot in the limited market of Uyghur-language pop.

Ablajan’s success makes him an important role model for young Uyghurs, with the lesson being not that they can all become pop stars, but that they can lead a modern, successful life without giving up on their culture and language. In an interview with Time magazine he said, “The message is that this is the 21st century … We cannot make a living buying and selling sheep.” It’s this kind of concern for social issues that distinguishes Ablajan from the ranks of anodyne Bieber-wannabes. While his music sounds like commercial pop, the lyrics often address social issues like pollution, the need for education, and the loss of traditional patterns of living. It would be a stretch to say his songs are political – they lack the nationalistic sentiments of the Uyghur folk songs popular in the 1980s – but they do give voice to the concerns of many Uyghur communities.

Having said that, these aren’t uniquely Uyghur concerns. The environment is one of the greatest worries of the Chinese public at present, as is also the rapid pace of social change throughout the country (especially in terms of the shift to urban life). In 2013 Ablajan started recording songs in Chinese as well as Uyghur, obviously primarily for commercial reasons, but with this comes the possibility that a broader (Han) Chinese audience might get to hear a Uyghur singer articulating similar concerns to theirs. If more people outside Xinjiang can recognise that this common ground exists, some might also look more sympathetically (or at least with a more open mind) at other grievances expressed by Uyghurs in Xinjiang. As Ablajan’s manager says, his music “can help bridge the divide between the Uighur and Han worlds … He can be a messenger of peace.”

Like many other Uyghur musicians in different genres, Ablajan is using a modern musical form that nonetheless remains indebted to older Uyghur musical forms like the muqam. This combining of traditional and modern styles is likely to play an important role in the preservation of Uyghur culture and language, and by extension, their identity. While Uyghur culture has been repeatedly targeted by the Chinese state, in many ways the ‘threat’ to Uyghur culture, if one perceives it as such, is just as great from globalising influences. In order to remain relevant, some growth and adaptation has to take place (as has had to occur historically). This isn’t to deny the importance of preserving Uyghur musical tradition. The famous tambur player, Mahmut Mehmet, has spoken of how when he listens to the muqam he remembers his grandfather, and his grandfather’s grandfather, and which minority he’s from, something that no other music can do. He’s entirely right when he says, “Music can represent a minority”.

But there’s more than one way to do this, as the documentary The Silk Road of Pop ably demonstrates. The film explores the vitality and diversity of the music being made by young Uyghur musicians in Xinjiang, focussing on the hip hop, rap and heavy metal scenes in Urumqi. Most of the groups involved in these scenes aren’t yet as popular as singers like Ablajan. As Sameer Farooq, one of the directors of the film told me, “What was common among all of the musicians we spoke with was a shared struggle to make a livelihood through their music. It was very difficult to get the rest of China to know/understand what was going on in terms of new music production in Xinjiang. There was an enormous initiative on the part of many groups to organize showcases on their own, bringing together a number of bands to hold a concert.”

The film shows that the music scene is at least one aspect of Urumqi society that isn’t ethnically divided. Adil, a rock band, has Uyghur, Han and Manchu members, many of the bands sing in both Uyghur and Chinese, and most importantly, a lot of the bands have a mixed fan-base. Farooq says that shows “draw thousands of young people from both the Uyghur and Han communities. The bands playing would also straddle many cultural groups. It was very encouraging to see that the audiences were mixed.”

Urumqi’s rap scene began in the early 2000s; many rappers cite the influence of Eminem and his contemporaries. By the end of the decade there was a thriving scene, with groups like Hei Bomb, Soul Clap, Xikar and EIG, who rapped in Uyghur, Chinese, Kazakh and even English. In an interview in 2008, EIG said ‘My name is EIG, I am 20 years old. Everybody calls me a genius, no can defeat me in English rap.’ After the 2009 Urumqi riots the music scene went quiet, due to a ban on public gatherings, and the inability to spread new music online, as the Internet had been suspended.

Of the groups performing currently, the most prominent is Six City (a reference to the six cities of south Xinjiang). Most come from the southern, poorer neighbourhoods of Urumqi, and have had to drive hospital shuttle buses and work in traditional Uyghur dance troupes to pay the bills. The group raps half in Chinese, half in Uyghur, partly for commercial reasons, but also, according to one of Six City’s members, because “the Chinese government censors less when you mix in Chinese lyrics.”

Like early hip hop in the US, there’s a focus on social injustice in Six Cities’ lyrics, albeit within boundaries. Rather than writing about ethnic discrimination, they focus on topics like drug and gambling problems in poor areas, and on the need for self-respect and pride in their culture. Despite the limits of what they can express, their lyrics can still be challenging. During an informal performance in The Silk Road of Pop, in early 2010, less than a year after the Urumqi riots, one member of Six City raps:

The rhythm of life is speeding up.

The rich have money, and they’re going out.

While the poor are still waiting.

Some are crying, enduring.

Often there are many fires.

To get it real, lies are exposed.

Don’t get excited. Just wait till dusk.

All the riots, all the cursing, for what?

For my home. I’m staying here.

While the song makes no reference to ethnicity or nationalism, for many Uyghurs its references to economic inequality, suffering, the call for transparency, coupled with the strong declaration of attachment to place, surely resonates.

Despite their different musical styles, Ablajan, Six City and other Uyghur groups have many things in common. One is that almost all of them, both in their music and in interviews, express an attachment to traditional Uyghur musical culture. Ttheir music isn’t intended to replace it, more to reinterpret it by filtering it through other musical styles. In many cases this is meant as more than a purely artistic project. For many of the groups, music is not only a way to comment on issues within Xinjiang, but also to engage with an international audience. As Eliar from Six City eloquently puts it:

“Every country, every ethnic group around the world is creating new ideas to help others understand their nation or ethnic group. They use all kinds of means. And us? Why do we want to do hip hop? Because we want the world to understand Uyghurs but we want to use a new method. If you go abroad to play dutar or tambur, maybe a small number of aficionados will know it is Uyghur music. But the average person won’t know. They won’t understand because they don’t listen to classic or folk music. Most young people want to listen to pop music. So the point is to put our culture into popular culture. Then when people around the world hear our song they will say, ‘Oh this is good, who is this? Six City. And what are they?” Uyghur. That’s the most important thing.”

Having a thriving Uyghur-language music scene also helps preserve the Uyghur language, which is being marginalised by an increasingly Chinese-dominated education system. Some Uyghur musicians have made an explicit effort to promote their language. In 2013 Ablajan wrote a song to help language learning, while the famous dutar player Abdurehim Heyit has recorded a version of the 19th century poem ‘Mother Tongue’. What makes the song particularly apt is that the poem was composed as a protest against the influence of Persian and Arabic in Uyghur education.

I will respect the person who knows his mother tongue

I will trade gold for the mother tongue spoken from their lips

Whether this mother tongue is in America or Africa

I will spend thousands of coins to go there (to hear the mother tongue)

Oh, mother tongue you are a mark left to us by our great ancestors

A song for language learning sung by a seven year old has also become popular. Berna, a child star from a wealthy family in Urumqi, along with another teen star, Gulmire Tugun, included a lot of linguistic and cultural information in an apparently simple children’s song. The lyrics demonstrate spelling patterns, grammatical rules, how words can be formed by combining letters, and perhaps most of all, the importance of loving one’s language.

Ba, Ba, Bring it for me

Bring the alphabet for me

If you take it from the people give it back to the people

Give it back to the people who love it

Give the language to the people who love it

Purchase it again for me, buy an Alphabet for me.

With knowledge (of Uyghur) prosper for me

Rise and soar for me.

At present, music and other cultural avenues are probably the safest way for Uyghurs to promote their language. Recent, more direct attempts have been curtailed by the authorities. In 2011 the linguist and poet Abduweli Ayup opened a Uyghur-language kindergarten in Kashgar, the success of which led him to try to do the same in Urumqi. Though there are numerous regulations for establishing private schools in China, Ayup presumably managed to follow these, as he was allowed to appear on state-run TV. According to one of his former students, he wasn’t against Uyghurs learning Chinese, “it’s just that he thought they should also know their own language.”

But for reasons that remain unclear, the Kashgar kindergarten was closed down in March 2013, apparently for lacking the correct permit. Ayup and his two business associates were arrested in August 2013 for ‘illegal fund raising’. The brother of one of the arrested men told the New York Times that they had been trying to raise money for a kindergarten in Tianshan, a poor, predominantly Uyghur district in Urumqi (where most of Six City come from). Exactly what was so ‘illegal’ about their fund raising activities was not specified – but they seem to have been engaged in such nefarious activities as selling honey and T-shirts.

The treatment of Ayup and his partners is illustrative of how limited the space for resistance of even the most peaceful kind has become for Uyghurs in Xinjiang. The increased restrictions on religion, the destruction of Uyghur neighbourhoods, and the continuing economic marginalisation of most Uyghurs means that the material and cultural welfare of Uyghurs is increasingly under threat. There’s little chance that government policy in Xinjiang is likely to become more tolerant in the near future in any of the areas that cause resentment.

Yet though a small number of Uyghurs may have concluded that there is no other way to resist except violence, musicians like Berma, Ablajan, and Six City all serve as examples of another way. They are representative of many young, city-dwelling, Chinese speaking Uyghurs who are forging a different kind of Uyghur identity, one that may be able to negotiate the pressures, constraints and contradictions of life in contemporary China (not all of which relate to being an ethnic minority). While embracing global culture, and looking outwards, some also retain a sense of their history and culture, and are struggling to ensure these remain both vital and relevant.

Nick Holdstock is the author of The Tree That Bleeds, which describes the year he spent living in Xinjiang. China’s Forgotten People, a book about Xinjiang and the Uyghurs, will be published by IB Tauris in May 2015. His first novel, The Casualties, will appear in August 2015. www.nickholdstock.com.

@NickHoldstock